Workbook 1

Ideas in action to help you say something

These are designed to help you review, critique and apply your own thinking.

Cases studies-based examples, based on my doctoral research interviews with community activists, charitable sector and NHS leaders. See my Prof thesis at Middlesex University here

Not quite safe enough – losing my voice

I am about to go on to a stage to run a session for 60 people. They are public sector advocates. Their job is to help people to speak up, to ‘whistle blow,’ without fear of victimisation. I have been invited by their manager, whom I met at a recent conference, where I was talking about my research into people who are ‘constructively awkward.’ She, along with her senior team, are in the audience today. My brief is to talk about what to do when you feel hopeless because no one wants to listen.

I had a bold opening written in my notebook:

We are here because you know that speaking up, openness and candour are not welcomed. We work in organisational cultures that enable or constrain the conversations we are trying to make happen. Cultures that teach us who can speak to whom about what. You are exhausted and frustrated, and these feelings are symptoms of the conflict we have about speaking up.

We should face a fact. Sometimes, no one wants to hear what you or the people you support have to say. You’re banging on the door, but no one is going to let you in, even though you can see them hiding behind the sofa.

With your help, I want to investigate this conflict. So, in the future, when frustration and exhaustion threaten, you don’t blame yourself or try to work even harder, but instead ask a question: ‘Why is this person, this issue so hard to hear?’

As I organised my notes, I caught my sponsor’s eye. She smiled. And as I began to speak, I realised that my bold voice was failing to show. It wasn’t a disaster, but my opening was bland. A moment of self-silencing, and an unrecognised connection between myself and the audience. Perhaps we were all wondering if it was safe enough to talk about how things really are? Not how we imagine or hope they are.

After the session I tried to work out why I had not stuck to my script, been more resolute. Why I had failed to say what I really thought. What was it about this situation that led me to wish to be so agreeable? I wrote some notes by way of evaluation, a few days later.

The eye-contact with my senior sponsor. I liked her and respected her intention to help her people, but this triggered a worry that I would say something she and her colleagues would find disruptive and difficult. Ironic, given the shared assumption that speaking openly is a good thing. I was anxious that drawing attention to the inconsistency in the role of public sector advocate would disrupt an assumed consensus (at least in my mind) that the role is welcomed, even by those who find themselves listening to uncomfortable truths.

This consensus hides an ugly truth. Despite many policies being produced about the importance of openness, since the Robert Francis report into whistleblowing in the NHS, [9] people are still victimised for speaking up. I know this because I have spoken to them and seen the harm done.

I was stifling a sense of futility. Why argue for the freedom to speak up if you do not also talk about how hard it is to listen? Hard because some issues are just problematic and messy, and some people who endorse advocacy can feel their status is threatened by what others have to say. The sort of people who dislike having their world view questioned.

My failure to name this inconsistency made it harder to argue that feeling hopeless is a normal response when others are determined not to listen, a fact often ignored.

The session was not a disaster. But it would have been better if I had taken more care, during

my preparation. My focus was on getting the content and slides right. I paid less attention to

protecting my capacity to speak. I should have anticipated the presence of the senior team and

the risk, that old feelings about knowing my place, in the presence of ‘authority,’ would surface

and strangle my voice

[10].

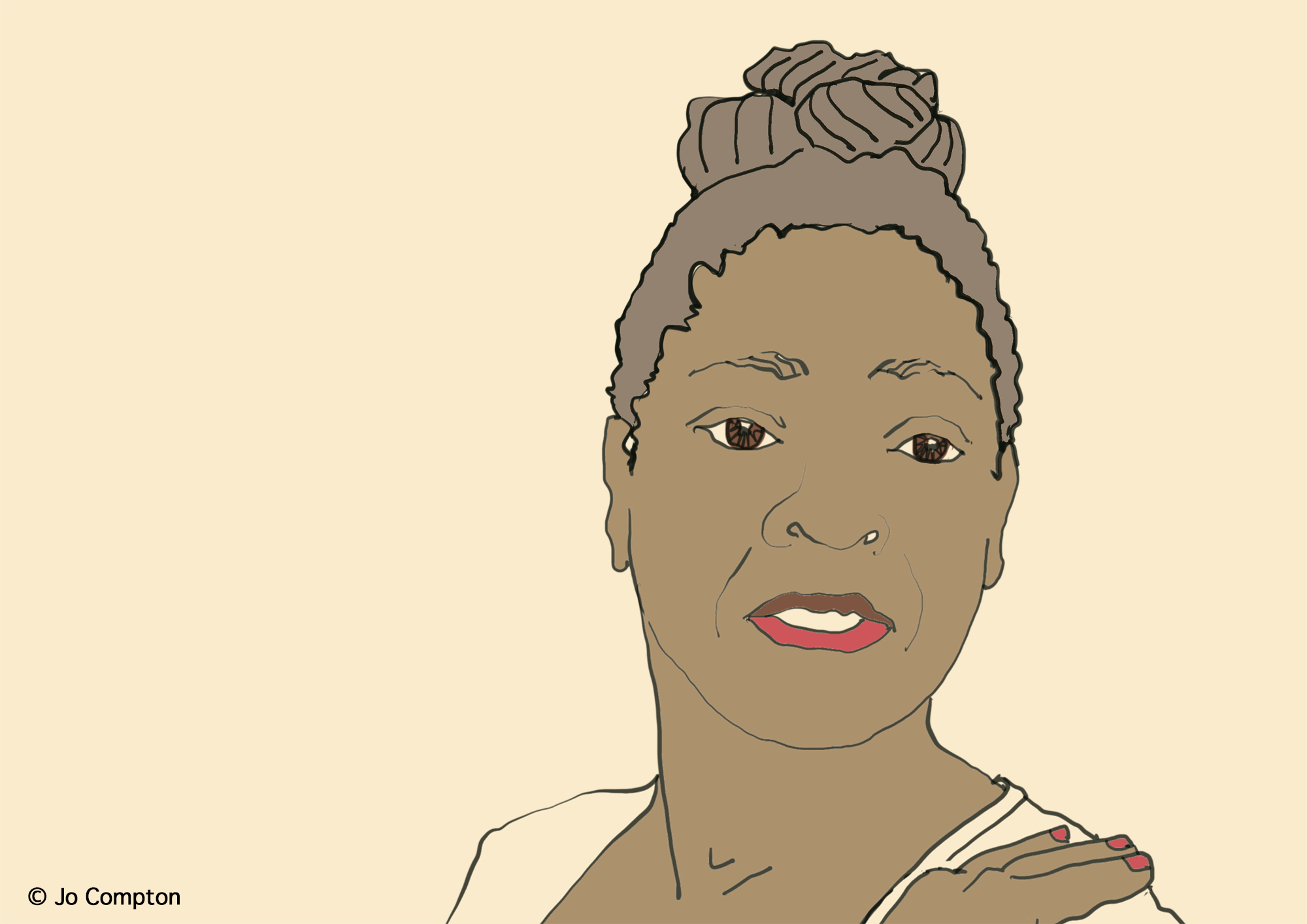

Constructive awkwardness in action - calling out racism

This example is based on an interview with Elaine. During the interview I asked her for an example of a time when she just knew she had to ‘speak up.’

Elaine was a community activist, journalist and a refugee from civil war. Now living in the UK, she was recently appointed to a local oversight group that brought together the public, private, voluntary and community sectors to co-ordinate local services. Primary-school performance was on the agenda.

Various reports measuring pupil performance had been tabled. Elaine noticed that the conversation had come to focus on migrant children and the assumed effect their collective performance was having on school performance overall.

As a refugee from war, Elaine was alert to this line of reasoning, involving the manufacture of a simple explanation for a complex challenge (‘it’s their fault, if they were not here this would not be an issue’).

(Un)fortunately for her colleagues, Elaine, like any good journalist, had studied the reports and knew the data. Her view was that the data did not support the emergent reasoning of the group. In her words, it was a case of ‘wrong thinking.’ Their ‘reasoning’ was, she concluded, racist. Her first intervention was to question aloud her understanding:

‘I think I’m hearing us blame the refugee children for these results. Am I getting this right?’

No response.

In a louder voice:

‘If we are blaming them, then isn’t this racist? And if it is racist, that wouldn’t be OK, would it? What about the needs of these children; how is this going to help them? It is just going to stoke up more racism. Is that what we want? I’m not sure you have any idea about what it’s like to be a target of hatred.’

Silence.

The chair of the meeting responded in an embarrassed tone:

‘No, that’s not our intention here. I’m sorry if that’s what you’re hearing. What do others think?’

To be constructively awkward is to worry less about what others think and feel. The intention is to disrupt emerging explanations before they become ossified (‘it’s the refugees…’); to create a pause, time to think, and consider other questions. And do this knowing that you are going out on a limb, may be left hanging, or evicted from the group.

Elaine went from knowing ‘something is not OK,’ via ‘Oh shit, I need to say something,’ to speaking in a way that got people thinking again (why are we thinking like this; what are we missing, avoiding…?).

In preparing herself to speak, she listened to her ‘internal voice’ – the reflexive voice we all have in our heads. (Read: When no one wants to listen)[11] The voice that runs a commentary on our thoughts and behaviour as we face uncertainty. The voice that helps us to consider the ‘what is being asked of me in this situation’ question.

Elaine’s response was shaped by her lived experience as a journalist, refugee and victim of a genocidal war. Silence did not feel like an option.

‘I knew I was going to speak but I did not do so immediately. I was full of rage. How dare they treat people like this? It was as if I was back home, being forced to leave. I was back in the trauma, sitting here in this stupid meeting, in safe old London, raging against another lot of mindless bureaucrats just doing their job’.

She described her conflicted state in a way that throws light on the wider struggle to speak:

- She was afraid of losing control of her rage yet knew she needed to mobilise it to overcome her silence and speak in a way others would hear as authentic.

- She was more worried her silence would be taken as agreement, than being labelled a troublemaker.

- She wanted to act as a self-determining adult yet not be evicted from the group.

- She wanted to use her personal experience to ground her intervention, yet to minimise the risk of flashbacks and feeling ‘emptied’ as a result.

- She wanted to keep relationships going and yet be true to herself – the refugee, journalist, warrior, activist, kind-hearted individual and survivor.

Elaine teaches us that speaking up is a complex act. It is not made more likely or possible by simply telling people to ‘be candid’ and ‘speak truth to power.’

Constructive awkwardness in action – helped to stop and think

My two colleagues and I are sitting in front of the group. It is the second day of a five-week leadership programme for community leaders. We had worked hard to get here. To secure the money and time, to run a programme, equal to the senior public sector leadership offers we direct. We had been talking to the group about developing a ‘reflective practice’, prior to organising into small groups. We were interrupted by Grant.

‘Do you know what it is like for some of us to be faced by three white programme directors?’

We stop talking. The obvious truth to some in the group, is now obvious to us. We looked at each other. I felt I was teering on the edge of being totally silenced. How could I not have noticed? Yet here I was in role; with two people I trust. As we have done previously when we don’t know what to do, we have a conversation with each other in front of the group.

‘We need to think about this. We need to think about difference, the obvious and the hidden how it is present, silent, and how we can use that fact to think about our leadership here and people’s leadership ‘back at work.’ Not sure how yet but let’s talk…’

It was not perfect but enough to acknowledge the moment. Grant’s intervention ensured difference, power, silencing, racism were now part of our shared agenda.

Grant’s question defines a dimension of constructive awkwardness. It was blunt, clearly delivered, surprising, authority-challenging, assumption-probing intervention. He sought to question our understanding of what we might represent as white directors to Black participants. In particular, to test our capacity to participate in conversations that explored how we might collectively re-create those aspects of life that some found oppressive. That as we asked them to critically reflect upon their behaviour, could we be trusted to do the same?

His intervention destabilised our normal practice; our way of seeing and being in the world. He created a stop, pause, think moment. The fact that we could think and respond, is indicative of another dimension of his skill in constructive awkwardness. The intervention was pitched in a way that facilitated, albeit uncomfortably, a collaborative enquiry. We were not the target, our lazy thinking and how that might constrain possibilities over the coming weeks was.

Grant was skilful in his use of rage given once again white people, in authority we trying to tell him what to do. I would assume he was angry. He could have chosen silence, avoid further reminders of how life really is. How people like us could be silent with no loss or power as we sat here, in this room in our well-respected organisation.

Mobilising rage

Frank has faced relentless racism both growing up and as an adult. Briefly, his rage led him to strike out at those who had treated him ‘as if I was scum.’ A mix of ‘rogue rage’ and ‘wipe rage.’

He came to an understanding that his life was being consumed by anger: his rage ‘faced both outwards and twisted inwards.’ Confronted by a respected leader and realising he was wasting his own potential as a leader; he changed the choices he was making. He told me what was said to him:

‘It’s easy to be destructive but it’s much more difficult to be positive. Are you going to try to be part of the solution?’

And he described his response:

‘It struck home with me. There’s no point just fighting, struggling, sitting with your own people and talking about the struggle. You must actually get out there and go into the places that you know need to be changed. That’s ultimately going to benefit your community.’

He described how his rage shifted, becoming a force that could sustain his relentless engagement with the very institutions that had treated him so badly.

Frank was and expert in the Race Relations Amendment Act and the duties it imposed on the people he often found himself sitting with. He was the best prepared in the room. Technically and through his skilful use of his (Lordean) rage to investigate the issues and disappoint (and therefore potentially bring into the conversation) those who assumed he was there just for pay back.

He assumed (as his mentor had) that more was possible. That how people thought and behaved, did not exhaust the possibilities of how they could think and behave as they carried out their duties. That it was possible to step aside from habitual ways of acting; that it was possible to notice and change the way the way work cultures ‘worked’ to determine people’s behaviour.

He was alert to his desire to be liked, to belong. He knew awkward people can be silenced by being co-opted, as if they are really ‘just like one of us’. He could keep his distance and still be engaged.

He, along with Grant and Elaine, were heard as tough, determined individuals, who meant them no harm, wanted to disturb, faced difference, sorted points of agreement and who asked good questions.

Disagreement as a way of connecting

Sulhara is a senior nurse. She described a conversation she had had with a senior manager two weeks after a fiery exchange in a meeting when she challenged his interpretation of the risk data.

‘I had decided to go for it. He countered, raising his voice, saying that it was me who was wrong. I said I was not wrong and took him line by line through the report.’

‘A few weeks later I phoned him up and asked him if he could help me. He said, ‘’you are one of the few people I’ve ever met who believes that having an argument is a basis for a good relationship.’’ I laughed and said, “I guess we know each other a bit better now”.’

Her story captures a surprising fact. Disagreement is a connection. And it can be built upon, as long as you keep talking. Sulhara’s skill was to resist being labelled as someone who was just ‘difficult,’ as someone who did not know their place. Someone who could be easily silenced.

It’s worth remembering that however skilled and well intentioned your interventions it still may be met with an attack. It can be useful to re-frame it in your head or out loud.

- You’re arrogant. No. I’m just determined.

- You’re stupid. No. I need more information, can you help?

- It’s not your place. OK, but my intention is to be helpful.

- You like to argue. Yes, just like you. This is important to both of us, so let’s talk some more.

- You’re too angry. No. This situation is not OK and it’s not about you.

The skills of constructive awkwardness include the willingness and words to repair things. As one interviewee said – ‘I gave it to them both barrels and next Sunday I had to use my sermon to apologise and remind them why this was such an important issue in the community. You have to know when to backtrack.’