Workbook 1

Background ideas to help you say something

To help notice, name and talk about what might be going on.

Understanding how I have learnt to use my voice

When you know you are going to have to speak up, your voice, tone and language are shaped by prior experience. What you have learnt about how someone like you, looking and sounding like you, should speak to whom about what. Evaluating and modifying this ‘learning’ enables you to loosen the grip of any constraints you feel in the present, to reduce the risk of going quiet (as I have done – see ‘Not safe enough’).

Use these questions to think about how your voice has been shaped, by recalling and examining moments and people who taught you (often with the best of intentions) how to speak ‘correctly’ in particular contexts.

- What was I told about how you should speak to people and which subjects were appropriate?

- Who taught me the rules of conversation?

- What happened if I questioned or broke the rules?

- What did I learn about arguing and managing difference between siblings, friends and people in authority?

- What did I learn not to say?

- Who and what helped me to express myself?

- What messages did I receive about my accent?

- What did I learn about how people in my profession should speak?

- How did I learn which subjects were appropriate for me to talk about?

- Who taught me the rules?

- What happened if I broke the rules?

- Who was I expected to listen to?

- Who was I expected not to question?

- What did I learn about how I should speak to whom about what?

- What events ‘helped’ me learn the rules?

- How do the rules differ for individuals (e.g. by seniority, ethnicity, sexuality or gender)?

- Who am I expected to listen to?

- Who am I expected not to question?

- How did I find out about the no-go issues/people/events around here?

- What happens if I question the rules?

- What happens if I break the rules?

Understanding how evolution shapes our voice

Being able to moderate your behaviour consciously is a skill and asset. You can enable collaboration. A situation where others, with different status and responsibilities, who think and feel differently, can speak more freely. Where people worry less about fitting in and agreeing. A place where people agree that collaboration, sharing ideas and thinking together, is where new ideas emerge.[4]

The neurological wiring will help you do the following.

- Quietly notice hierarchy in the room. If your boss is present, you will think before you speak. You may not risk spontaneity or saying anything that contradicts what you imagine their thinking – more so if their boss is also present.

- Assume that being in a group is safer than being on the outside, on your own. You know that in a hostile environment, it is better to be part of a group – and some work environments are hostile.

- Moderate your behaviour to ‘fit in’ – to the extent that you may hear yourself agreeing to a ‘fact’ or decision you know to be wrong. [5]

- Moderate your behaviour to avoid the conscious experience of the anxiety we risk being swamped by when we fear being evicted from ‘our’ group.

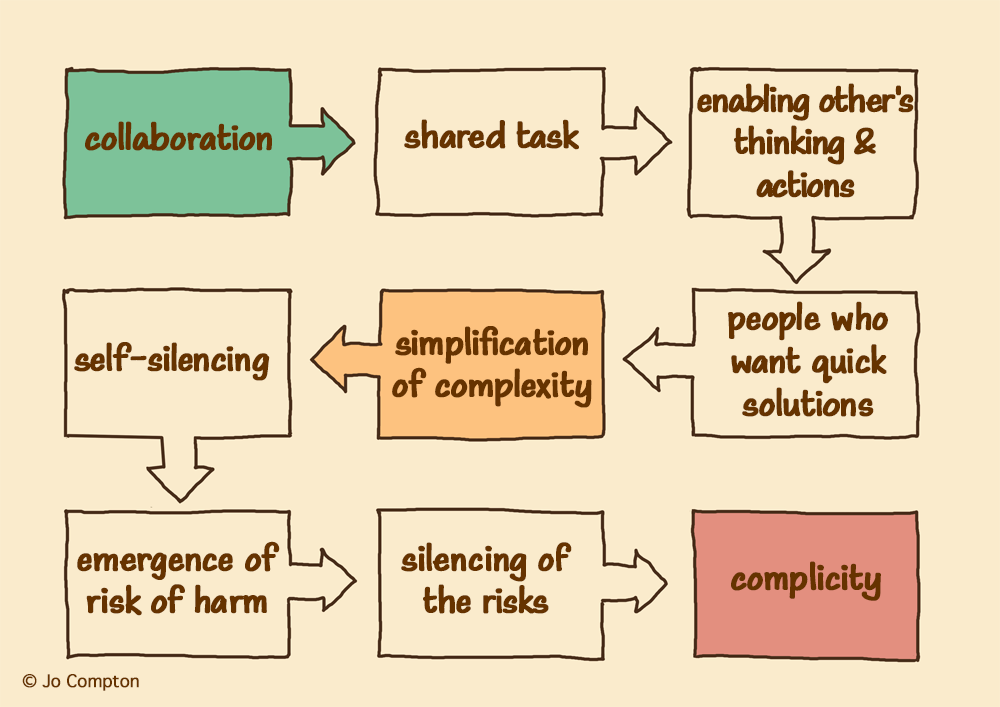

Collaboration can be fragile when people are under pressure to deliver solutions to complex problems. Without attention, it can slip into complicity. [6]

- We often start well, expressing our ideas and assumptions. We build a sense of safety as we come together in our differences. Senior and experienced people model the desirability of taking a step back to openly question themselves and others about their thinking and behaviour.

- Then a subtle pressure is applied to individuals in the group. People are pulled back to their teams and managerial accountability. The tension between collaboration and being compliant with the thinking and behaviour of the home team is hard to manage. Slowly, openness closes, safety evaporates, compounded by the difficulty of speaking openly about this tension.

- Finally, people return to self-silencing. Ideas are not expressed, concerns are buried. Half-baked plans are agreed, and the safety gauge passes amber.

Mobilising rage to get heard

Rage doesn’t get a great press. It is rarely mentioned in organisational life or literature. But like love, rage is all around. Why else is there intractable bullying and harm within our organisations?

Rage is troubling. It suggests a lack of self-control. But while self-control and ‘emotional regulation’ are necessary skills, rage is enabling.

The expert on rage is Myisha Cherry. She writes that ‘those who bear the brunt of racism and oppression most directly don’t get the luxury of ignoring these problems, peaceful as it might be to spend a day without worrying about them.’[7] She contends that anger, a component of productive rage (Lordean rage – see below) is enabling, helping us face facts and act. The qualities of the constructively awkward practitioner.

Like silence, we need to read rage so we are not trapped by it. It needs to become something we notice and talk about, even if only in the privacy of our heads.

Cherry describes five types of rage.

- Rogue rage – what I feel when I know I have been treated unjustly. The target of my anger is not limited to the person or organisation I think responsible – I hold everyone responsible. A small step towards hating everyone.

- Wipe rage – what I feel when ‘that lot over there,’ who look and sound different, are doing this to ‘us.’ We believe that they, who we thought owed us a duty of care, have ignored, disadvantaged and abandoned us. So, we just want to wipe them out. We won’t hear any arguments to the contrary.

- Resentment rage – what I feel when I have no power because ‘that lot over there,’ who look and sound different, have it all. I hate them and I wish I were one of them. I cannot get them out of my head. I’m the victim and there is nothing I can do but hate.

- Narcissistic rage – I’m really special and should be treated as such. So, when you and the pathetic system you represent doesn’t treat a person who looks and sounds like me properly, I’m going to make sure I let you know.

The rage I heard the people describe, that I interviewed for my research, is identified by Cherry as ‘Lordean rage’ after activist, professor and poet Audre Lorde (1934–1992).

- Lordean rage – I feel my rage, but I’m not so taken over by it that I cannot think. I focus it to act ‘without the desire to harm or pass on pain.’[8] My purpose is to fight injustice.