Workbook 2

Background ideas to help you say more

To help notice, name and talk about what might be going on.

Why is it hard for me to listen?

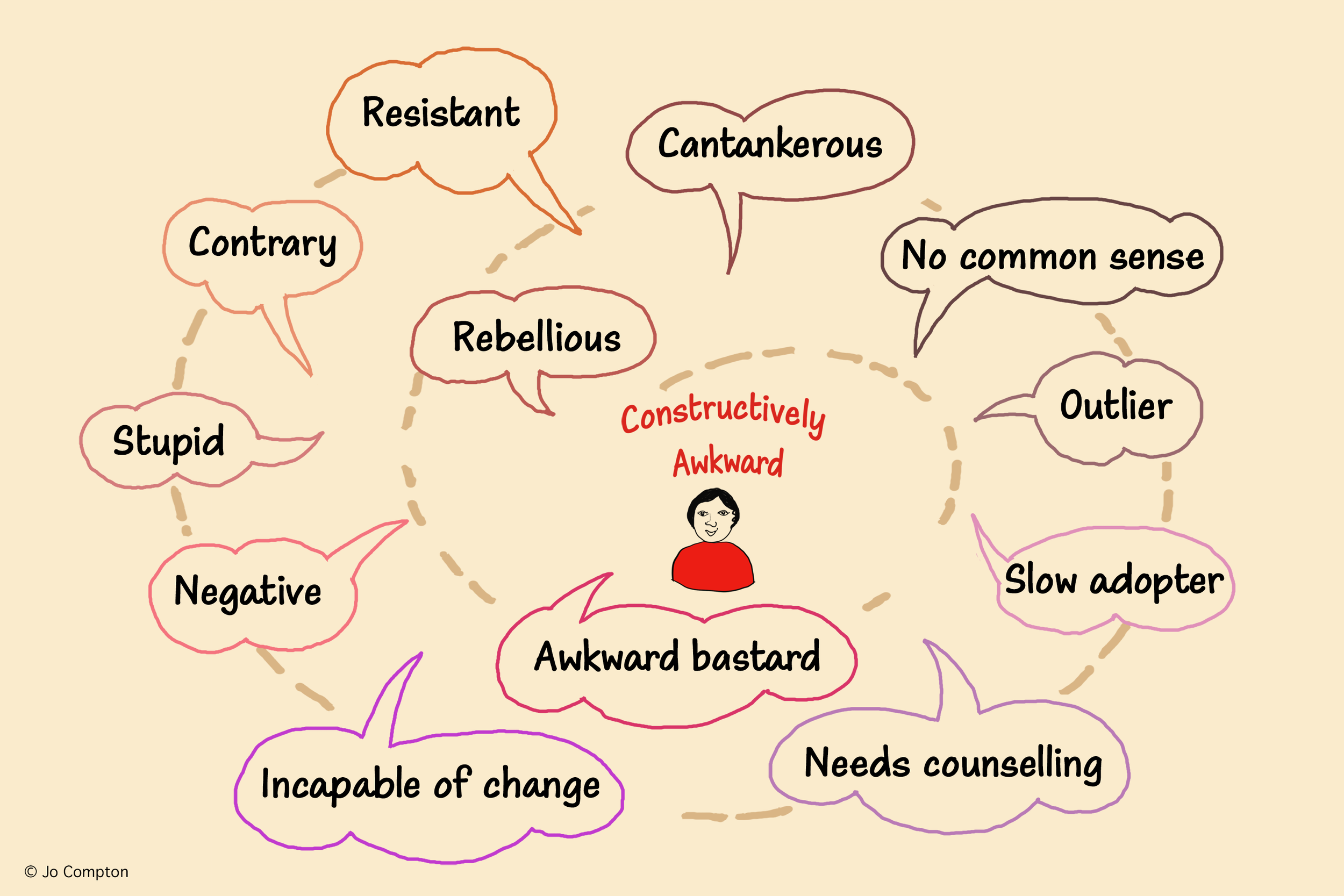

It’s OK to feel ambivalent about someone who challenges you. But notice the words you use to label people who question you.

You may be the only person in your team who knows and feels the full pressure to deliver. The skill is to acknowledge your ambivalent feelings, while believing that the challenger, in their own clumsy way, is also trying to do their job and speak to what they know. They are trying to be ‘constructively awkward’ (How to speak up and get heard); and of course, you may be wrong or misinformed.

One reason speaking is a challenge is that we can find it hard to listen. Being honest about this challenge does not mean assuming all that is said is useful or valid. It is to assume that deciding what is or is not relevant, to the issue under discussion, is not the prerogative of the few but the outcome of argument and collaboration.

Recognising bad leadership

Bad leaders tolerate and use bullying and incivility to police the boundaries of the conversational culture and to sabotage psychological safety. Such leaders require docile followers, whose silence is self-imposed, self-policed and heard as agreement.

Inquiry reports, and our own political history, teach us that effective leadership must not be taken to mean that good is being done. Bad things happen, cloaked by the language of ‘righting wrongs’, ‘accountability’ and ‘efficiency.’

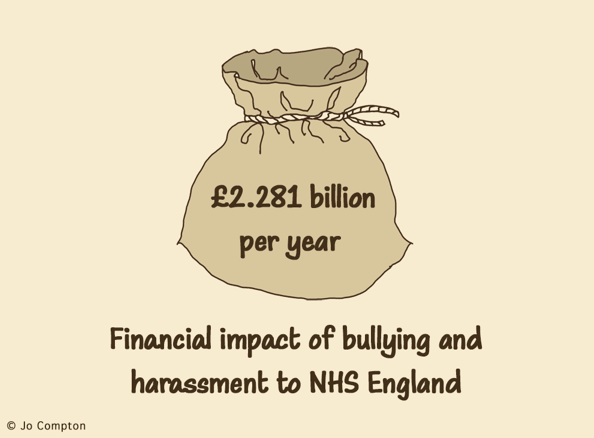

It’s worth noting, bad leaders cost us all. [3]

These descriptors will help you to notice and name bad leadership, including your own.[4]

- Incompetent – lacking in skill and will

‘I’ll just run the meeting like I always do, people know what I want.’

- Rigid – unwilling to adapt

‘Look, we’ve tried all that. This is the right way. Get on with it.’

- Intemperate – lacking self-control

Don’t ever say that to me again in a meeting. Who do you think you are? Just bring me solutions.’

- Corrupt – putting my interests before yours

‘Let’s leave that out of the report – I/we cannot be seen to fail.’

- Callous – being uncaring and unkind

‘We don’t have time for this. Just get on with it or get out. You knew it was going to be tough when you joined. Stop moaning.’

- Insular – showing a disregard for others

‘You’re my team. That lot over there are of no interest to me. We’re on the right track, we’re so near, we are not giving up. Ignore them, they are useless anyway.’

- Evil – intending harm

‘Round them up, they are what’s wrong. They are not like us.’

Bad leaders, like any leader, communicate their intentions through conversation and language. Bad leaders are encouraging, cajoling, rude, uncivil and bullying.

- Rudeness – a lack of manners, discourteousness, impolite, insensitive or disrespectful behaviour by a person who has a lack of regard for others.

- Incivility – rudeness or unsociable behaviour/speech that occurs with ambiguous intentionality.

- Bullying – seeking to harm, coerce, torment, or intimidate someone who is perceived as vulnerable.

- ‘I’m just being clear’

- ‘you need to be more resilient’

- ‘we are a high-performing team, what did you expect?’

Such behaviours are often ambiguous in their intention, particularly if obscured by saying:

Silence as a consequence of exhaustion

Exhaustion can be misunderstood as a sign of personal failure. An explanation that risks the silencing of the ‘victim’ by inducing shame or shaming.

Current approaches to exhaustion can gag any inquiry into the link between this intensely personal response and the choices made – by whom and why – to organise work in a particular way.

Exhaustion is never adequately explained by talk of the need for ‘personal resilience.’ The substantive issues are:

- Why do people need to be so resilient around here?

- How do we organise work differently and still succeed?[5]

Below are questions to open up a conversation about exhaustion, this silent and hidden issue in the workplace. Doing this can open a line of inquiry about how work could be organised differently and still deliver. Remember, the current way work is organised is unlikely to exhaust all the ways it could be productively organised.

If people feel safe enough, these questions can create a quiet moment of thought and perhaps the expression of feelings. They are questions that demonstrate your interest as a leader in helping people to think about difficult stuff.

To make progress on these issues consider the following.

- What is my own experience of exhaustion?

- What choices do people have when they cannot do any more?

- How did I learn how to talk about those times when I have nothing more in the tank?

- How does this inform my approach to others?

- Why is this aspect of people’s work experience silenced?

- How does this silencing happen?

- Why does it happen and who benefits?

- Who or what is silenced and lost from our work conversations as a result?

- What small changes could I make to improve things?

- What could I change about the way I behave towards others?

Silence as a consequence of feeling like an imposter

Another reason we silence our know-how and cut ourselves off from conversations is that we believe we are an imposter – that we are somehow not good enough to have an opinion or contribute.

‘A chronic feeling of inadequacy in spite of repeated success.’[6]

This is a common experience. A reason why people are quiet. Therefore, to help people speak (and yourself) you have to make it ok to talk and investigate in a way that includes the wider context in which this intensely personal experience arises.

Consider the following.

- What is it about this situation that might have triggered the feeling of being an imposter?

- What is it about this situation that none of us fully understand?

- What have been my recent achievements? Make a list of them.

- What qualification(s) do I have that others would recognise and might find hard to achieve? List them and look at any certificates.

- If I accepted that I was good enough, what would I be saying about this issue?

- Who benefits from me feeling like an imposter?

- What evidence do I have that I’m the only one feeling stupid?

- What would make it safer for me to say more about this issue?

Silence as a consequence of being nice

Another reason people mute their voice is a desire to be nice - ‘we are the team who get along: we never fight; we really like each other’.

It may be true, but there is a consequence: people in this situation are less likely to question each other. A sort of shared pro-social silence develops that hinders critical awareness. A toxic niceness.

This is the group that acts as if the real purpose of their work is to comfort and protect each other from some real or imagined threat. And they do this by obliterating individuality and maintaining silence. Nothing must be said to disturb the calm waters

You can feel really bad about disrupting this kind of team culture. You are asking people to wake up and think about two inter-dependent requirements: getting the job done and sustaining good working relationships.

When ‘niceness’ silences and prevents people from speaking up, it means they have slipped into focusing only on maintaining good working relationships. But the recipients of the team’s work lose out. New ideas never get heard and conflict and differences, which may expose gaps and possibilities, are silenced. This is a culture that is unsafe for everyone.

A ‘niceness group’ is hard to break from. It’s nice, after all, to be liked and comfortable. But the price is one’s individuality and agency. Plus, it’s not what we are paid for.

In the end someone must ask questions. If it’s you, then try the following.

- What is our history – has something bad happened that still shapes how we talk and work together?

- What are the threats, pressures and work demands that our group is facing?

- How do we talk about this reality?

- Who or what could we be ignoring or silencing by our behaviour?

- What are the benefits for us of being nice?

- What are the downsides?

- What one small change could make it safer to speak about our differences?